The Economic and Environmental Role of Honey Bees: A Historical Exploration

Did you know that honey bees are not native to North America and they were originally imported from Europe in the 17th century? Plymouth, the home of our organisation, is world famous for its history of commercial shipping, handling of imports and passengers to the Americas ever since the Mayflower Pilgrims departed for the New World in 1620. Melita Hoskin is a Third Year BA English and History student at the University of Plymouth who has dedicated her spare time to researching the important role of honey bees throughout history. In this article she explores some pivotal moments for the honey bee whilst also visiting the modern day climate crisis, something that threatens the very existence of all pollinators and biodiversity as a whole…

‘Bees [are] the 800-pound gorillas (most dominant force) of the pollinator world.’

Their role in the protection of the environment is unparalleled; it is now common knowledge that humanity would not survive without them. Climate change activists have made protecting the bees one of the forefronts of the movement, and they are now symbolised as a protector of the natural world. It is only fitting that many activists have made it their mission to protect the bees in return - because they are the gateway to the literal blooming of the natural world. But how did European honey bees arrive in America, and who engineered their growing populations?

Early Transportation of the Honey Bee To America

There is no record of European honey bees on the world-famous Mayflower, the cargo ship that brought the pilgrims to Massachusetts during the Great Puritan Migration in the 17th century. Historians assume that the ship was too full of other necessary items to fit a beehive. The earliest record of European honey bee transportation was on the 5th December 1621; ‘By the Council of the Virginia Company in London and addressed to the Governor and Council in Virginia, “Wee haue by this Shipp and the Discouerie sent you diurs [divers] sortes of seedes, and fruit trees, as also Pidgeons, Connies, Peacockes Maistiues [Mastiffs], and Beehives.’ The ship mentioned is likely to be ‘The Discovery (60 tons, Thomas Jones, captain, and twenty persons) [which] left England November 1621 and arrived in Virginia March 1622.’

There are little to no historical documents with explicit numbers of how many European honey bees were transported, so historians are still making guesses on how bees thrived throughout the centuries in America, but ‘the total amount of beeswax exported from Virginia in 1730 (just over one hundred years since the first import of honey bees to North America) was 156 quintals, equal to 156,000 kilograms, or about 343,900 pounds.’ This large amount just a Century after the first transportation indicates that they did thrive economically and environmentally, flourishing in ways that directly contrasts to the declining populations today, but enforces their significance throughout the centuries.

An Asset to the Planet

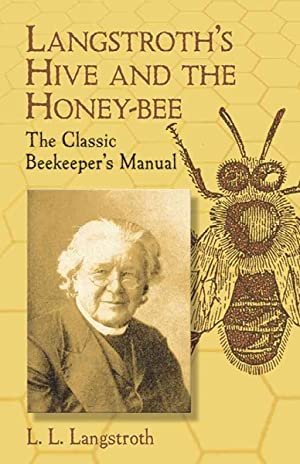

It was Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, regarded as the ‘father of American Beekeeping,’ who advanced beekeeping in America. In his book, A Practical Treatise on the Hive and Honey-bee, Langstroth praised the honeybee, claiming that they were ‘well appointed commonwealths,’ ‘galleries of art,’ and that they provided ‘truth and virtue.’ The parallels between favourable, reputable traits, such as democracy, honesty, and craftsmanship, and the art of beekeeping indicate that the symbolism of bees throughout history have always been maintained. The climate change movement uses these pre-existing motifs and symbols to defend bees and to rally for more support. Their transition from economic necessities to environmental symbols is not so straightforward as it seems - bees are still being readily supported because of their economic purposes as well as their roles in defending the environment.

During the 17th-18th Century in America, their colonies had frequently been admired, and beekeeping became respectable employment; not only was it crucial to the economy, but essential in beauty products and other material goods. Bees were still symbolised centuries ago, but their value stemmed from their economic purposes. Honey could be used for the obvious - as a natural sweetener - but it also ‘has had a valued place in traditional medicine for centuries.’ Their multipurpose led to their continued transportation and their growth; there was no Native American word for Bees; instead, they were nicknamed ‘White Man’s Flies’. Such a nickname adds to the evidence that the transportation of the European honey bee was crucial towards modern European honey bee populations; within two centuries, Langstroth had transformed American beekeeping into what we know today with the creation of the Langstroth beehive.

The Climate Crisis and the Role of Bees Now

From the first transportation of the European honey bee in 1621, to Langstroth’s modernisation of beekeeping in the 19th century, the journey of the honey bee has been lost in modern-day discussions over the climate crisis and the role of bees now. The little documentation of such journeys proves that we were all underprepared for the huge crisis that bees face today. But if we look back to a time when the European honey bee’s value was mostly economic, we can appreciate their environmental value even more through the complex journeys and environments they undertook to arrive at the symbolic honey bee fronting campaigns for climate change activism.

The ecosystem has changed drastically - and still will continue to change. Climate change is one of the key drivers of the decline of bees globally. Some wild bees and other pollinators have only a small temperature window where they can live. When temperatures rise, they are forced to head to colder climates to seek refuge, reducing the overall territory they can inhabit, and reducing population sizes. This can have ripple effects on the surrounding ecosystem. The COP26 Conference at Glasgow last year, one of the most significant conferences for environmental sustainability, pledged that it will ‘support adaptation, reduce climate vulnerability, promote biodiversity, and enhance livelihoods. To achieve all this, we need to halt and reverse deforestation,’ and they will ‘aim to increase global awareness of the critical role of protecting, conserving, and restoring nature and ecosystems for climate change adaptation and mitigation, including forests and biodiversity.’

Insects are estimated to contribute over £400 million a year to the UK economy and €14.2 billion (£12 billion) a year to the EU economy through pollination of crops. Nevertheless, a recent survey in the UK (Royal Mail 2015) found that over the past decade, interest in bee conservation has increased, with 80% of respondents reporting that they care (including scientific advances in bee research), however fewer than half could name a single bee species and only 3% knew how many species live in their country.

As the race to net zero heightens in its significance, and the voices pressuring world leaders to promise tangible change and progress grow louder, is there enough time to protect bees and the world’s most important pollinators?

RESEARCH SOURCES:

Rebecca Hirsch (2020) Where Have All the Bees Gone? Pollinators in Crisis, Minneapolis, Lerner Publishing Group, p. 25

Kingsbury, S. (1906) ‘The Records of the Virginia Company of London The Court Book’ Manuscript in the Library of Congress 1619 – 1622 Vol 1. Washington: Government Printing Offic, p. 532

Langford, T. (1662 [2015]) “Ships to America – Virginia 1622.” ‘American Plantations and Colonies’ http://english-america.com/places/va162.html#1622 [accessed 19/06/2021]

Pryor, E.B. (1983) Honey, Maple Sugar and Other Farm Produced Sweetners in the Colonial Chesapeake. Accokeek, Maryland: The National Colonial Farm Research Report, P. 20

Langstroth, Lorenzo Lorraine. A Practical Treatise on the Hive and Honey-bee. (United States, J.B. Lippincott, 1884) p. 8

Zumla, A., & Lulat, A. (1989 ‘ Honey- A Remedy Rediscovered’Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 82(7), London: Sage Publications, p. 384

Pellett, Frank Chapman. History of American Beekeeping ( Iowa: Collegiate Press, Inc, 1938)

Venis, S. (2021) ‘’5 Reasons Why Saving the Bees Is So Critical for Both People and Planet’ https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/importance-of-bees-biodiversity [accessed 08/07/2021

United Nations, (2021) ‘COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact’ https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf

United Nations, (2021) ‘COP26 Glasgow Negotiations Explained,’ https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Negotiations-Explained.pdf#page15

Kellar, B. (2011) ‘Honeybees Across America’ https://www.losangelescountybeekeepers.com/history-of-honey-bees-in-America [accessed 30/08/2021]

Ransome, H. (1937) The Sacred Bee in Ancient Time and Folklore, Boston: Houghton Mifflin C, p. 260

Venis, S. (2021) ‘’5 Reasons Why Saving the Bees Is So Critical for Both People and Planet’ https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/importance-of-bees-biodiversity/ [accessed 08/07/2021]

Ross, S. (2017) ‘Defending the Bee: The Emblem of Manchester’ https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/magazine/features/defending-the-bee/ [accessed 26/08/2021]

Wilson, J. S., Forister, M. L., & Carril, O. M. (2017)’ Interest exceeds understanding in public support of bee conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment,’ 15(8), Wiley: New Jersey, p. 460